Mileage tax is a slush fund for transit

Saturday, April 16, 2022

|

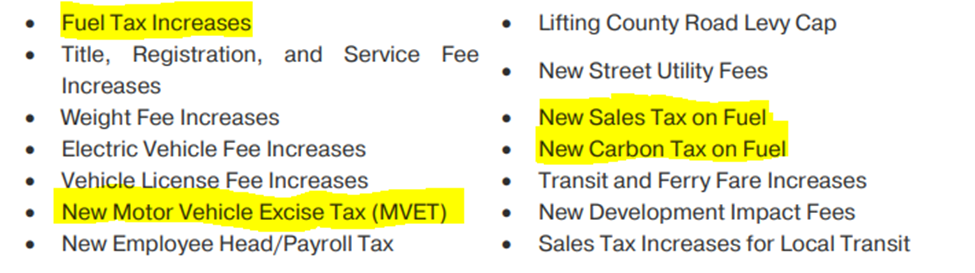

By MARIYA FROST Planners from the Puget Sound Regional Council, the region’s metropolitan planning organization, have updated their Transportation 2022-2050 plan. Despite the impact and uncertainty created by COVID, they still intend to price people out of cars and try to prod them onto transit, which is still down about 40% riders compared to 2019-20. They see the Road Usage Charge (RUC) – a per-mile tax with massive revenue potential for government – as their golden ticket to achieve that goal. At a February meeting of the Washington State Transportation Commission (WSTC), the PSRC’s executive director, Josh Brown, advocated for a sky-high RUC that would price people out of cars and amply fund transit expansion. While the WSTC advocates for a 2.5 cent RUC – comparable to the 49.4 cent per gallon gas tax drivers currently pay – the PSRC plan assumes a variable rate as high as 10 cents per mile during peak hours and 5 cents off peak (a type of congestion pricing). A 10-cent RUC is equivalent to a $2.00 per gallon state gas tax. That doesn’t include the federal fuel tax of 18.4 cents per gallon that drivers pay as well. Here is how that plays out practically. Let's say your car gets the state average of 20.5 mpg and you drive 10,000 miles per year. Under a state gas tax (49.4 cents per gallon), you pay $241. Under a theoretical 10-cent RUC, you'd owe $1,000. If the state credits back the fuel tax you paid as they promise they will, you'd still owe about $760 in RUC. Under a 5-cent RUC, after the gas tax credit, you'd still owe about $260 in RUC. Either way, the PSRC’s preferred rate would impose significantly higher costs on drivers than the current gas tax or the WSTC’s proposed 2.4 cent RUC rate. Additionally, the PSRC would like the RUC to not only be layered with congestion pricing that shifts the RUC rate depending on time of day, but it would also like the revenue use to be flexible and not constitutionally restricted for spending on roads alone. "The reason we’re calling for a flexible Road Usage Charge in our plan is because when we look at investments needed at the local level and transit investments, the revenue has to come from somewhere. If it doesn’t come from a Road Usage Charge...how do you then fund these other items?” Brown mused. He assumes “these other items” the PSRC wants to fund, including massive transit expansion, are all necessary. “Our viewpoint in our plan is that it’s better to fund a transportation system with flexible funding sources than to limit yourself, especially in our region where we need to make substantial investments to support a great transit system…If you’re limiting yourselves because of constitutional provisions then you’re going to limit the ability to have a really efficient transportation system” he noted. For the PSRC, the RUC is an opportunity to move away from a users-pay/users-benefit principle, represented in our state’s constitutionally protected gas tax, and to move toward a system where drivers pay a high cost for their trips, the money goes into a general pot, and politicians and planners decide how best to spend it. It has absolutely nothing to do with drivers paying their “fair share” for their impact on roads as technology advances and vehicles become more fuel efficient. Brown said, “If you go back to the beginning – why did PSRC, years ago, say that we needed an alternative funding source? Initially, it was a systemwide tolling approach. It then morphed into some type of VMT i.e. the Road User Charge. It was because we knew years ago, that in order to address climate change, we needed to decarbonize the transportation system, period.” Brown reasons that decarbonization of the transportation system means the gas tax cannot be depended on as a funding source, since decarbonization efforts would deplete it. In fact, the PSRC appears set on making driving completely unaffordable for ordinary people by increasing the fuel tax, and imposing both a carbon tax and sales tax on fuel. This doesn’t include increases to various vehicle fees that drivers would have to pay annually when they renew their registrations. Taking the PSRC’s logic to its natural conclusion, largely wealthier owners of electric vehicles would be able to buy their way out of this expensive system and continue driving wherever and whenever they want. Rural and suburban middle and low-income residents would have their mobility severely limited as they would be stuck paying extremely high costs for fuel. Their alternative would be to cut hours out of their day to sit on public transit, which is slow, inflexible, and increasingly less safe. Brown and his colleagues at the PSRC claim to care about equity, yet their plan restricts mobility and relegates middle and low-income people to living in crammed spaces near transit. This is equity on planners' terms, not those of ordinary people. Government should not be in the business of predicting and controlling what people want and doing so by imposing financial hardship. They should be in the business of creating an environment where people can choose what they want – where they live, where they work, how they travel. Further, rather than simply including impacted community members in conversations about what government planners intend to do anyway, and calling that equity, transportation officials should empower community members to have a higher level of freedom in making their own mobility choices. The PSRC’s plan is wishful thinking at best, and harmful and inequitable at worst. Lawmakers and other decisionmakers who care about transportation policy in the Puget Sound should reject the PSRC’s vision for a costly, restrictive RUC and demand a pause on the PSRC’s approval of this plan (scheduled for May 26th), as suggested by transportation expert John Niles during today’s PSRC Transportation Policy Board meeting. This would give the PSRC time to resolve major problems in the plan and develop realistic, meaningful, short-term goals that increase, rather than limit, our freedom of movement.